Introduction

Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) stands as one of the most pressing global health challenges of our era. At its core, AMR occurs when microorganisms—such as bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites—change in response to the drugs designed to destroy them, rendering our treatments ineffective. In simpler terms, these microbes become resistant to the drugs that once held the power to annihilate them.

Transitioning from mere scientific jargon to a global concern, this resistance escalates the risk of disease spread, severe illnesses, and even death. Imagine a world where a simple bacterial infection, once easily quelled by antibiotics, becomes an untreatable ailment. Alarmingly, this is not a mere projection into a dystopian future; it’s the sobering reality we are gravitating towards.

The danger looms large. If unchecked, AMR threatens to dismantle decades of medical progress. The drugs we’ve relied upon, the bedrock of modern medicine, may soon be rendered obsolete. This is not just about a remote possibility; it is an urgent call to action.

In the forthcoming sections, we will delve deep into the intricacies of this looming crisis. But let it be clear from the onset: the battle against AMR demands global attention, concerted efforts, and immediate action. The clock is ticking, and the stakes couldn’t be higher.

The Rise of AMR

We must first unravel its basics to grasp the magnitude and urgency surrounding Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR). At its essence, AMR denotes the ability of microbes to withstand the effects of drugs—essentially, they become ‘resistant’ and the medicines lose their potency. This isn’t a random occurrence but an evolutionary response to the drugs themselves.

Historically, when exposed to an antimicrobial drug, susceptible microbes perish, but those resistant to it survive, multiply, and subsequently take over. Over time, if drugs like antibiotics are used recklessly or excessively, this resistance can escalate at a concerning rate.

Several factors are propelling the rise of these drug-resistant infections:

- Over-prescription of antibiotics: Often, antibiotics are prescribed even when unnecessary, such as for viral infections, against which they have no effect.

- Incomplete treatment regimens: Patients frequently stop using antibiotics once they feel better, not completing the full prescription. This incomplete treatment gives microbes a chance to develop resistance.

- Overuse in livestock and agriculture: Large volumes of antibiotics are often used in agriculture, which can seep into our food and water supply, leading to indirect antibiotic consumption.

- Easy availability: In several regions around the world, antibiotics can be purchased without a prescription, promoting indiscriminate use.

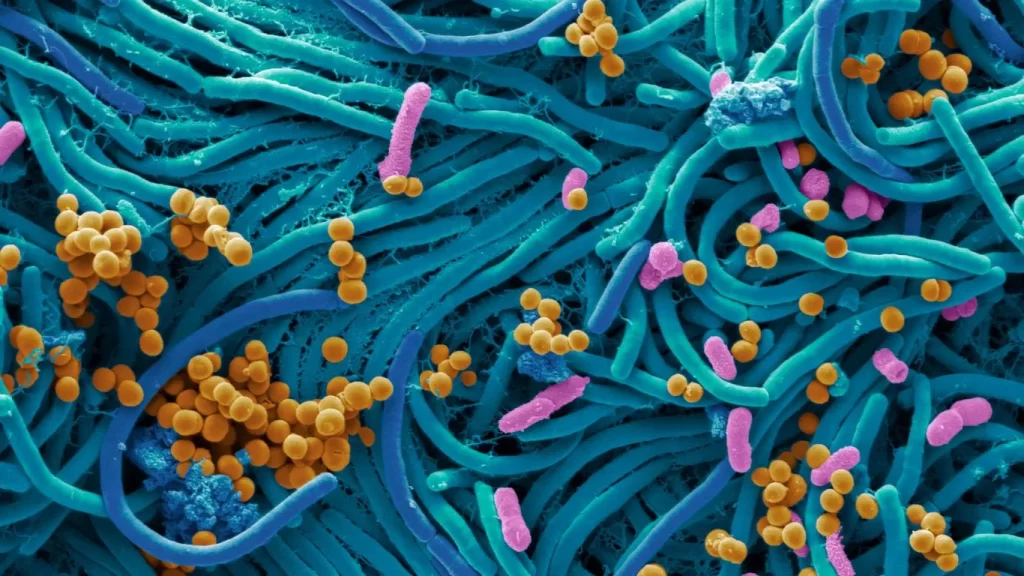

The culmination of these practices leads to the emergence of what is popularly termed ‘superbugs’. These formidable microbes are resistant to multiple antibiotics, making infections caused by them notably difficult to treat. The emergence of superbugs is no longer observed solely in clinical settings. They have begun infiltrating community settings, casting shadows on the larger realm of public health.

Moreover, the repercussions of this proliferation go beyond just individual health. Hospitals experience longer patient stays and higher medical costs due to treatment failures and increased interventions. Economically, AMR strains national healthcare systems and incurs significant societal costs.

It is crucial to underline that AMR isn’t a distant, abstract concern but a clear and present danger. Addressing this issue demands not only an understanding of its genesis but also a commitment to act against its spread.

Why It’s Not Just About Viruses

Often, when discussing Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR), a common misconception arises, suggesting that this phenomenon solely pertains to viruses. In reality, the scope of AMR spans beyond viruses, encapsulating a variety of microorganisms, prominently including bacteria.

Bacteria vs. Viruses

At their core, bacteria, and viruses differ fundamentally. Bacteria are single-celled organisms that can live in diverse environments, from soil and water to the human gut. Many bacteria are benign or even beneficial, aiding in processes like digestion. On the other hand, viruses are smaller than bacteria and require living hosts—like humans, plants, or animals—to multiply and survive. They invade cells and exploit them to replicate, often leading to diseases.

Antimicrobial drugs designed to combat bacterial infections are known as antibiotics, while those targeting viruses are antivirals. Though both types of drugs are essential, bacterial resistance to antibiotics has emerged as a particularly pressing issue.

The challenge with bacterial evolution is its rapid pace. Bacteria reproduce swiftly, and in the presence of antibiotics, the resistant ones thrive, multiply, and dominate. This evolutionary prowess, combined with the overuse and misuse of antibiotics, creates a potent mix. For instance, when antibiotics are inappropriately prescribed for viral infections, they don’t aid recovery. Instead, they attack benign bacteria in the body, providing an environment for resistant bacteria to flourish.

Additionally, the persistent use of these drugs, even when unnecessary, trains bacteria to withstand them. Just as one might practice building resistance against the cold by frequently exposing oneself to it, bacteria, through constant exposure to antibiotics, become more adept at resisting them.

The Bigger Picture-AMR

When we talk about Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR), it’s essential to see the issue beyond the confines of clinics and hospitals. AMR unfurls its tendrils into wider domains, leaving imprints on the environment and highlighting the complex tapestry of interconnectedness among humans, animals, and antibiotics.

Environmental Implications

Our environment plays a pivotal role in the story of AMR. Residues from pharmaceutical industries, hospitals, and agricultural run-offs often find their way into water systems, introducing antimicrobial drugs and resistant microbes into freshwater sources. Not only does this pose direct threats to aquatic life, but it also means that these resistant strains can enter our food chain, multiplying the challenges we face.

Another concern is waste. Improperly treated waste containing antibiotics can breed resistance in the environment, acting as hotspots for the spread of resistant microbes. The environmental dimension of AMR underscores the need for tighter regulations on industrial discharge, waste management, and agricultural practices.

The One Health Approach

The issue of AMR doesn’t exist in isolation—it’s intricately woven into the fabric of our global ecosystem. This recognition has given birth to the One Health approach, which posits that the health of humans, animals, and the environment are intrinsically linked.

Consider this: antibiotics are extensively used not only in human medicine but also in veterinary practices and agriculture. Animals treated with antibiotics might carry resistant bacteria, which can then transfer to humans through consumption. Likewise, the use of antibiotics in crops can lead to residues lingering in our fruits and vegetables.

The One Health perspective urges a holistic strategy, promoting coordinated efforts across multiple sectors. By understanding how AMR affects and is affected by each of these facets—human, animal, and environment—we stand a better chance at devising effective countermeasures.

Addressing the Crisis-AMR

Confronting the colossal challenge of Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) demands a robust, multi-pronged approach. Tackling this menace requires both reactive strategies to manage existing issues and proactive measures to stem its future growth. Let’s explore the diverse avenues that are currently being traversed to address this crisis.

Current Strategies

- Stewardship Programs: Central to the fight against AMR, these initiatives aim to ensure the judicious use of antibiotics, both in clinical and agricultural settings. By focusing on the right drug, dose, and duration, stewardship programs actively reduce the unnecessary use of antibiotics, thereby slowing the pace of resistance development.

- Infection Prevention: By minimizing the spread of infections in the first place, we can reduce the need for antibiotic treatments. Simple yet effective measures, like hand hygiene and vaccination, play a pivotal role in this preventive approach.

- Global Health Collaborations: AMR knows no borders. Its global nature necessitates international cooperation. Collaborative efforts, such as data sharing on resistant strains and best practices, are crucial for a coordinated response to this shared threat.

Exploring Solutions

- Vaccines: One of the most promising avenues in the fight against AMR is the development and use of vaccines. By preventing infections, vaccines reduce the need for antibiotic treatments, subsequently diminishing the chance for resistance to develop.

- Novel Treatments: While antibiotics have been the cornerstone of bacterial infection treatments, there’s a growing interest in alternative therapies. Phage therapy, which employs viruses that infect and kill bacteria, and the use of antibodies are some of the innovative treatments under exploration.

Hurdles in New Antibiotic Development-AMR

Developing a new antibiotic is a resource-intensive and time-consuming process. The last few decades have witnessed a stark decline in the introduction of new antibiotics. The reasons are manifold, including scientific challenges in discovery, limited financial incentives for pharmaceutical companies, and stringent regulatory barriers. Yet, with the growing threat of resistant superbugs, the urgency for new drug development has never been more visible.

To navigate these challenges, a global cooperative framework is paramount. By fostering partnerships between governments, academia, and private sectors, and by prioritizing funding and research in this area, we can reinvigorate the pipeline for new, effective antibiotics.

Conclusion

Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) isn’t just a problem for health professionals or policymakers; it’s a looming shadow that affects us all. As we navigate this vast and intricate landscape of resistance, it’s abundantly clear that the responsibility to address this crisis doesn’t rest on a single entity’s shoulders but is, in fact, a collective endeavor.

We live in an interconnected world, where the consequences of our actions, no matter how seemingly minute, reverberate in profound ways. Whether it’s the decision of a physician to prescribe an antibiotic, a farmer’s choice to use them in livestock, or an individual’s commitment to complete their full course of treatment, every action counts.

However, action is invariably preceded by awareness. Staying informed about Antimicrobial Resistance, understanding its implications, and recognizing the gravity of the situation are foundational steps. As consumers, patients, or just concerned citizens, our decisions—driven by knowledge—can make a meaningful difference.

Beyond personal practices, it’s also crucial to champion systemic changes. Support policies that advocate for responsible antibiotic use, rally behind research that seeks alternatives and endorse global initiatives aimed at curtailing the spread of resistant strains.

In the face of such an imposing challenge, it’s easy to feel overwhelmed or insignificant. But remember, AMR grew out of myriad small decisions and practices. Similarly, its solution will emerge from countless informed choices and collective actions.

Let’s not be passive observers in this narrative of resistance. It’s time to act, be proactive, and together, rewrite a story that speaks not of a daunting crisis but of resilience, foresight, and global unity.

FAQs About AMR

AMR threatens effective disease treatment, leading to prolonged illness, increased mortality, and higher healthcare costs.

Bacteria evolve in response to antibiotic exposure, enabling some to survive and replicate despite the drug’s presence.

Superbugs are bacteria that have become resistant to multiple antibiotics, making infections harder to treat.

Individuals can take prescribed antibiotics as directed, avoid self-medication, and practice good hygiene to prevent infections.